This week an op-ed by former White House budget director Peter Orzag ran in The New York Times. The piece called for immunity for doctors in medical malpractice lawsuits if the doctor followed a set of specified “evidence-based guidelines” for treatment.

Orzag is a pretty talented number cruncher and budget maven but the proposal is both scientifically and legally illiterate.

As a lawyer, I read Orzag’s op-ed and it’s not even clear that he understands what he’s proposing. Orzag talks of medical “immunity.” Well, in the legal field when we talk about immunity, we mean something that precludes someone from ever bringing suit against an entity. So, one traditional form of immunity – the doctrine of “sovereign immunity” – precludes litigants from filing suit against the federal government or a state government unless the government has consented to the filing of such lawsuits (this consent often comes in the form of a law saying that the government can be sued for certain kinds of torts). Another type of immunity is diplomatic immunity: the immunity from lawsuits that attaches to the representatives of foreign governments. When sovereign immunity or any type of immunity applies, it is a “do not pass go” situation – your lawsuit is dead upon filing and never gets to proceed to a jury.

By both his use of the word “immunity” and his admiring references to the 1972 Social Security amendments, Orzag seems to favor full-blooded immunity for doctors who follow “evidence-based guidelines.” But at other points, when Orzag speaks of doctors “demonstrating” that they followed “evidence-based guidelines,” he seems to be proposing that the guidelines, rather than providing doctors with complete immunity, would serve as a so-called “affirmative defense” for them. Unlike immunity, an affirmative defense does not bar a lawsuit from its outset; instead, an affirmative defense is something that can provide a total defense only at the end of a lawsuit, after there has been fact-finding. One traditional affirmative defense is that of “assumption of risk.” So, for example, if a skydiver dies in a skydiving accident and the skydiver’s survivors allege that his death was due to the skydiving company’s negligence in, e.g., picking a landing site, the skydiving company might rely on an affirmative defense of “assumption of risk,” stating that skydiving is an inherently dangerous activity, that the skydiver knew the risks of the activity before he jumped and that, therefore, they should not be held legally responsible for the skydiver’s death. Unlike a case with an immunity defense that precludes the plaintiff from ever getting through a courtroom’s doors, an affirmative defense is a defense that is typically applied by a jury at the conclusion of a lawsuit.

There’s a big difference between providing doctors with a form of “immunity” in medical malpractice lawsuits and providing them with a new affirmative defense to such lawsuits. If doctors have limited immunity from medical malpractice lawsuits based upon their following “evidence-based guidelines,” they could invoke this protection on their say-so. When a lawsuit was filed against them, they could simply file a motion saying, “I followed the guidelines,” and the lawsuit against them would be dismissed, without any more investigation or inquiry. A plaintiff would not even get a chance to prove that the doctor was lying and that the doctor actually ignored any such guidelines; the lawsuit would simply be doomed from the outset.

On the other hand, if these hypothetical “evidence-based” guidelines were simply an affirmative defense, a plaintiff would get a chance to challenge whether the doctor in fact followed the guidelines and, if the doctor followed the guidelines, he could rely upon them as a defense. Under this regime, medical malpractice lawsuits would hardly be any different than they are today. Today, doctors accused of medical malpractice will frequently rely on medical treatises and other medical authorities to show that their treatment conformed to the standard of care.

So either Orzag is proposing a radical reform of medical malpractice liability, one which would deprive patients of their rights on a doctor’s mere say-so, or he is proposing something that would not make much of a dent in the costs of medical malpractice lawsuits (because the guidelines could only be invoked after discovery in a lawsuit, once the defense lawyers have billed for hundreds of hours of defense work and because the “reform” would not be that drastically different from the state of the law today, where doctors can invoke treatises and other medical authorities in their defense).

Assuming that what Orzag is proposing is the more modest reform of permitting these “evidence-based guidelines” to be relied upon as an affirmative defense, we have to address the question of: Is this (more modest) reform a good idea? It seems unequivocally clear to me that the answer to this question is “No” and that Orzag’s beliefs to the contrary are rooted in ignorance of the practice of medicine and the scientific enterprise generally.

One of the dangers of having one supreme set of “evidence-based” clinical guidelines is that the practice of medicine will become fossilized. Secure in their knowledge that they are following the “right” course of treatment, doctors won’t feel prodded to develop new treatments or therapies. In time, such a regime will inevitably elevate and exalt the “old way” of doing things as sacrosanct. Young doctors who step outside the framework will be exposing themselves to massive liability, even if they have developed a better framework for treatment.

Orzag’s proposal also overlooks the extent to which there is disagreement among medical professionals about the proper standard of care. In virtually every medical malpractice lawsuit (except for the most cut-and-dried cases of mistake), there are expert witnesses on both sides who will disagree about the proper standard of care. The defendant doctor will inevitably drum up an expert who agrees that the proper standard was followed. Medical malpractice plaintiffs have to have their own experts and these experts often testify that the standard of care was different than the negligent doctor had supposed: that research has moved along or progressed since the treatment used by the negligent doctor was developed and that now a new standard applies throughout medicine.

From a legal perspective, Orzag’s proposal is a bit of an incoherent jumble. But however you interpret it, it seems like a bad idea.

You can read more reaction to Orzag’s op-ed here, here and here.

Monthly Archives: October 2010

From Around The Legal Blogosphere

- Professor Alberto Bernabe agrees with my assessment of the CVS inhaler situation: there would be no duty under the common law. Prof Bernabe also provides a link to some musings by Jonathan Turley about the tort defenses available to someone who forcefully took an inhaler from the pharmacy to help the woman.

- Professor Bernabe also highlights Duke Law’s “Voices of American Law“: a great series of mini-documentaries on important recent Supreme Court cases.

- Most joggers’ biggest roadway fears is being hit by a car. But Tom Vanderbilt highlights a recent case where a bicyclist fatally struck a jogger. This incident and others raises the question: can multi-use paths be shared safely by cyclists and runners? Or should cyclists have their own paths?

Babies Drowning In Puddles, CVS Pharmacists And Duties Of Care

Having studied philosophy as an undergraduate, I remember arriving at law school and quickly being disabused of the idea that my law school experience would be something akin to “The Paper Chase,” with imperious law professors kicking about mind-wracking hypotheticals. I think I learned this sometime in the first week of my first-year torts class, where we studying intentional torts and I deployed a thought experiment concocted by the philosopher John Searle: a man resolves to kill his enemy and gets into his car to drive to his enemy’s house, where he believes his enemy to be. En route to his enemy’s house, he accidentally runs over his enemy, who was out for a jog and who had darted in front of the car. Was the killing intentional? I remember asking the professor if a claim for an intentional tort like battery could lie on those facts, since Searle’s hypothetical appeared to fulfill all of the elements of battery, and was quickly reminded we were not there for a philosophy seminar: we were there to learn legal principles and learn how to use them to predict the outcomes of realistic cases.

Having studied philosophy as an undergraduate, I remember arriving at law school and quickly being disabused of the idea that my law school experience would be something akin to “The Paper Chase,” with imperious law professors kicking about mind-wracking hypotheticals. I think I learned this sometime in the first week of my first-year torts class, where we studying intentional torts and I deployed a thought experiment concocted by the philosopher John Searle: a man resolves to kill his enemy and gets into his car to drive to his enemy’s house, where he believes his enemy to be. En route to his enemy’s house, he accidentally runs over his enemy, who was out for a jog and who had darted in front of the car. Was the killing intentional? I remember asking the professor if a claim for an intentional tort like battery could lie on those facts, since Searle’s hypothetical appeared to fulfill all of the elements of battery, and was quickly reminded we were not there for a philosophy seminar: we were there to learn legal principles and learn how to use them to predict the outcomes of realistic cases.

About the only time legal education delved in the world of completely fanciful hypotheticals was in the hoary tale of the baby drowning in a puddle. The baby drowning in a puddle hypothetical runs like this: A man comes upon an infant, unknown to him, drowning in a shallow puddle. No one else is around and the baby will drown if the man does not act. The man can save the baby without any danger to himself, but does not act. The man walks away and the baby drowns. What tort has the man committed? None. As noted by one law professor in a recent law review article, “…there is a virtually universal consensus throughout the common law world that no duty is owed the baby in these circumstances.” In the absence of some legally cognizable relationship between them, people have no duty to act to help strangers.

The baby-drowning-in-a-puddle case is sort of an unusual legal principle because it’s not based upon any cases. There is no case of Smith v. Jones, where a baby drowned in such a puddle. It’s really straight out of the realm of the imagination.

And it’s not unfamiliar to philosophers. In his famous essay, “Famine, Affluence and Morality,” the Princeton ethicist Peter Singer argued that if you believe that it is morally wrong for a man to allow an infant drown in a puddle, you must believe it is morally wrong not to act to help those in the Third World. Other philosophers, like Peter Unger, have added their own embellishments to this thought experiment/hypothetical.

A few years ago, Singer published a book entitled: “The Life You Save: Acting Now To End World Poverty” that collected some real-life examples of babies drowning in puddles: police officers in Manchester, England who watched a ten-year old drown in a pond, instead of attempting to save him (because “they had not been trained to deal with such situations”) and many other scenarios where people walked past a virtual “baby in the puddle.”

All of this is offered as sort of a run-up to a story this week about a CVS pharmacist who refused to sell a $21 asthma inhaler to a woman in the midst of a life-threatening asthma attack who only had $20. You can read about the story here. According to the reports, while this woman flailed on the ground, the CVS pharmacist refused to give or sell her the inhaler because she was short by a little over a dollar.

It’s a fairly remarkable story and, unfortunately, the news reports leave unanswered a lot of questions, including: 1.) Were there other people around? Why didn’t they do anything to help? 2.) Was this CVS her pharmacy? 3.) What, if any, physical injuries did she suffer?

As much as the tort reformers and others say that we have too many lawsuits and people can sue for practically anything in America, this poor asthma-stricken woman, even if she had died, might have as few legal remedies as a baby in a puddle. So, I’ll toss it out there to the legal minds of the blogosphere: What viable claims might this woman have? (Let’s assume, to make it more interesting, that she died as a result). What other facts would you like to know? For anyone who wants to do the statutory research – are there any state statutes analogous to EMTALA that might have required a pharmacy to dispense emergency care to her?

Medical Malpractice Lawsuits: A Red Herring In The Health Care Debate

Courtesy of Alex Tabarrok, I had my attention drawn to a great series of blog posts by Austin Frank and Aaron Carroll, over at The Incidental Economist, on the subject of, “What Makes The US Health Care System So Expensive?”

Courtesy of Alex Tabarrok, I had my attention drawn to a great series of blog posts by Austin Frank and Aaron Carroll, over at The Incidental Economist, on the subject of, “What Makes The US Health Care System So Expensive?”

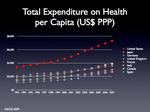

As Carroll noted in his initial post on the topic, part of the explanation for why our health care system is so expensive is that health care spending rises with a country’s wealth (a point I’ve previously blogged about here). Once people have the wealth to take care of the basics like food and clothing and shelter, they start spending more on maintaining their health and extending their lives. So part of the explanation of why we spend so much more on health care (compared to, say, a country like Bangladesh) is that we have so much greater wealth.

But that’s the obvious and, as Carroll points out, uninteresting part of the explanation. The really interesting part is that if you graph a country’s health care spending with its wealth, there is almost a perfect line of correlation, a direct proportion between a given increase in wealth and a given increase in health care expenditures.

The US, however, is a huge outlier. It sits far above this line of correlation, spending much more on health care than you would predict given our level of wealth. We spend about two to three hundred percent more on our health care than other wealthy countries like Germany and Japan.

In seeking to explain why we spend so much on health care, Carroll examines a series of red herrings – conventional scapegoats for the high cost of health care that really have nothing to do with why health care is so expensive. One red herring examined by Carroll is medical malpractice lawsuits. Drawing on the same Health Affairs data that I have previously blogged about, Carroll puts the entire cost of medical malpractice lawsuits (including the cost of so-called “defensive medicine” at about 2.4% of total health care spending.

Only about one-fifth of that 2.4% figure is attributable to actual payouts and defense lawyer costs in medical malpractice cases; the rest is spending that, as Carroll points out, may have a benefit to the patient. The extra test or procedure will sometimes detect a disease or problem before it manifests itself, lowering the treatment cost.

As Carroll, the economist, concludes, “[Medical] malpractice is not the root cause of our cost problem, and tort reform isn’t the solution. I wish it were that easy.”

It’s time we focus on the real problems in health care, including the “fee-for-service” model that the Health Affairs article cited by Carroll says dwarfs the spending on medical malpractice lawsuits and the hard-to-calculate defensive medicine costs. Villainizing medical malpractice lawyers and the victims of medical malpractice is not going to bring our health care costs down and it certainly won’t take care of the victims of medical malpractice.

I encourage you to read Carroll’s blog series on your own, as it is too difficult to encapsulate all of the insights into a single blog post.

The Health Care Mystery of Grand Junction, CO

If you set the time machine to “Way Back,” you may remember a blog post of mine about Dr. Atul Gawande’s New Yorker article, “The Cost Conundrum: What a Texas Town Can Teach Us About Health Care.” If you recall, the article was about why McAllen, TX had the second highest per capita Medicare spending of any city in the country.

If you set the time machine to “Way Back,” you may remember a blog post of mine about Dr. Atul Gawande’s New Yorker article, “The Cost Conundrum: What a Texas Town Can Teach Us About Health Care.” If you recall, the article was about why McAllen, TX had the second highest per capita Medicare spending of any city in the country.

The cost of living and doing business is much higher in a place like, say, New York but yet McAllen was ranked number two in the nation. Could McAllen’s high rate of Medicare spending be explained by demographic factors? Maybe people in McAllen were more obese than in other cities or had higher rates of hypertension?

By comparing McAllen to the nearly demographically identical city of El Paso some fifty miles away, Dr. Gawande was able to rule out the possibility that especially unhealthy lifestyles were responsible for the lavish spending in McAllen. The Medicare spending in El Paso was only half what it was in McAllen ($15,000 compared to $7,500).

Dr. Gawande ultimately concluded that the reason that health care cost so much in McAllen is that doctors had transformed it from a profession into a business; they were out to line their pockets with kickbacks that would be considered unethical in most cities, rather than to provide the patient with the amount of care needed.

In studying the Medicare spending levels of different cities, Gawande also identified cities that provided excellent health care for a fraction of the spending seen in McAllen. Two of these cities were Rochester, MN (where the Mayo Clinic is located) and Grand Junction, CO.

Both cities had excellent doctors but why health care spending should also be so low in these two cities remained a bit of a mystery. Now, the New England Journal of Medicine has published an article entitled “Low-Cost Lessons From Grand Junction, Colorado,” that delves into that mystery. Some of the reasons for Grand Junction’s low-cost success include the relatively plentiful number of primary care physicians, insuring that patients get more face time with their doctor; equal reimbursement rates for Medicare and private insurance (meaning that Medicare patients are less likely to have to go to an ER to get specialist attention) and payment of primary care physicians for hospital visits (making it more likely patients get to see doctors they are referred to).

It is clear that medical malpractice lawsuits are not contributing to the runaway cost of health care in our country. When Dr. Gawande went to interview the doctors in McAllen, they blamed medical malpractice lawsuits too. But, due to strict caps on pain and suffering in medical malpractice lawsuits that Texas had passed five years earlier, the number of medical malpractice lawsuits that Texas doctors faced had dropped “practically to zero.” The McAllen doctors admitted to Dr. Gawande that they were being disingenuous in blaming medical malpractice lawyers. Reforming health care requires the kind of creative thinking done by Dr. Gawande and should not be focused on blaming medical malpractice lawyers or limiting the rights of medical malpractice victims.