If you had to guess what hospitals, over the period of 2004-2008, billed Medicare for the most spinal fusion surgeries what hospitals would you name? Number one on the list – Johns Hopkins – probably would not surprise you. It’s a massive teaching hospital and one of the finest hospitals in the country. Number two on the list – UCSF Medical Center – wouldn’t raise many eyebrows either. Again, a massive teaching hospital.

If you had to guess what hospitals, over the period of 2004-2008, billed Medicare for the most spinal fusion surgeries what hospitals would you name? Number one on the list – Johns Hopkins – probably would not surprise you. It’s a massive teaching hospital and one of the finest hospitals in the country. Number two on the list – UCSF Medical Center – wouldn’t raise many eyebrows either. Again, a massive teaching hospital.

But you might be taken aback a bit by who occupies the bronze medal space on this podium: Norton Hospital in Louisville, KY. The story of how a backwater hospital in Kentucky came to bill Medicare for $48 million in spinal fusion surgeries was recently told by Wall Street Journal reporters John Carreyrou and Tom McGinty in the latest article in the Journal’s “Secrets of the System” series (which uses publicly available Medicare data to uncover possible fraud and waste).

As the Journal article notes, spinal fusion is one of the most hotly debated surgeries in medicine. It involves fusing together two or more vertebrae in the hopes of alleviating a patient’s back pain. A number of orthopedic surgeons contend that fusion surgery is only indicated for a small number of patients with back pain. Other surgeons, such as the team at Norton Hospital, find spinal fusion to be useful in a much wider set of cases, including cases where the patient is suffering from disk degeneration due to aging.

The disagreement among surgeons about the usefulness of spinal fusion would only be an arcane medical debate if some surgeons weren’t being paid millions of dollars by medical device makers for promoting the use of their hardware. The hardware used in a single spinal fusion surgery runs into the tens of thousands of dollars (“You can easily put $30,000 of hardware in a person during a fusion surgery,” says one medical professor quoted in the piece). Last year a half-dozen surgeons at Norton Hospital earned more than one million dollars apiece from hardware manufacturer Medtronic.

The payments – which some characterize as “kickbacks” and some call “royalties” – are supposed to be for contributions that the Norton Hospital doctors made to the development of the hardware technology. But the innovations for which the doctors supposedly receive these payments are slight; in a day and age when virtually anything can be patented (a patent is meaningless; it’s whether the patent stands up to a challenge that’s important) some of the Norton Hospital doctors receiving millions aren’t named on any patents. Critics contend that the payments are really kickbacks paid to the doctors for getting their colleagues and others to use Medtronic products.

Thanks to pressure by Sen. Chuck Grassley, Medtronic now discloses “royalty” payments to doctors on its website. If you have a question about whether Medtronic is paying your doctor for his work with the company, you can discreetly check by using Medtronic’s Physican Registry, now available here.

Of course, if your spinal fusion surgeon receives payments from Medtronic, all that information will also be buried somewhere within the informed consent packet that the surgeon has you sign prior to surgery. That boilerplate, as one back fusion patient detailed in the Journal story learned, is a virtually ironclad defense in some cases where patients were injured by medically unnecessary surgeries. Assuming that a doctor, prior to performing an operation of dubious necessity, has disclosed all of his financial interests to the patient and his care in performing the surgery did not fall below that of the ordinary surgeon, you will have a very hard time with a medical malpractice lawsuit even if you were injured and only subsequently learn of the troubling conflict of interest raised by the doctor’s surgeries and the medical device payments.

Ultimately, the Journal story should not be a surprise to the readers of this blog. We’ve seen how doctors in McAllen, TX bilk Medicare for unnecessary tests and procedures, we’ve seen doctors bilk insurers for unnecessary cataract surgeries and we’ve seen dialysis centers who have developed techniques to squeeze every last penny out of Medicare. It’s all part of the fee-for-service model that is driving up our health care costs.

Category Archives: Medical Malpractice

Medical Malpractice And Car Accidents: A Tale Of Two Public Health Problems

In 2009, 33,963 Americans died in car accidents. 100,000 Americans are killed each year by medical errors. Given the large number of lives lost to both medical malpractice and car accidents, both qualify as important public health problems. But while we are making strides in reducing the number of lives lost in car accidents, a recent study shows the number of deaths due to medical errors has held steady over the past decade. The divergent outcomes in these two areas may be due to the different approaches we take with respect to curbing car accidents and medical malpractice deaths.

In 2009, 33,963 Americans died in car accidents. 100,000 Americans are killed each year by medical errors. Given the large number of lives lost to both medical malpractice and car accidents, both qualify as important public health problems. But while we are making strides in reducing the number of lives lost in car accidents, a recent study shows the number of deaths due to medical errors has held steady over the past decade. The divergent outcomes in these two areas may be due to the different approaches we take with respect to curbing car accidents and medical malpractice deaths.

From 2005-2008, the number of traffic deaths declined twenty-two percent. What explains this precipitous drop? As reported last week by The Wall Street Journal, researchers at the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute think they have some of the answers. They chalk up the decline of car accident deaths to a combination of factors, most notably improved safety technology, more aggressive treatment of drunk drivers and stricter licensing requirements for teens.

When you look more closely at some of these factors – improved safety technology, aggressive prosecution of drunk drivers – they are largely the result of government regulation and resort to our court systems. Many car safety improvements are the result of government mandates and product liability litigation. And harsher treatment of drunk driving requires that our courts have more involvement in our lives.

While traffic deaths due to certain factors – such as distracted driving – are climbing steadily, we can see the way that society is dealing with that threat: we are passing more and more laws banning texting while driving or talking on the phone and driving. In short, when it comes to car accident deaths, we are not afraid to unleash the legal system to address problems.

But we seem to be doing the exact opposite when it comes to medical errors. We have lax regulation of medical technology, which leads to the problems you see here, here, here and here.

And instead of holding doctors legally accountable for medical malpractice, the tort reformers have us passing caps on pain-and-suffering in medical malpractice cases, caps that have virtually eliminated lawsuits against doctors in many states. Are insurance companies really going to insist that doctors implement error-avoidance technologies when the insurance have to shell out so little even in the minority of lawsuits where patients are successful?

The decline in traffic deaths that we’ve seen over the past several years is probably attributable to a lot of things – including people not being able to afford gas and therefore driving less. But the long-term graph of traffic deaths is clearly trending downward. And perhaps there’s a public health lesson in that.

Medicare’s Dialysis Program: An Illustration Of Why US Health Care Costs Are So High

Over the past month an article written by Robin Fields and originally printed in Pro Publica has attracted a great deal of attention and earned a reprint in The Atlantic. The article, about Medicare’s dialysis benefit, illustrates the problems at the heart of much of American health care.

Over the past month an article written by Robin Fields and originally printed in Pro Publica has attracted a great deal of attention and earned a reprint in The Atlantic. The article, about Medicare’s dialysis benefit, illustrates the problems at the heart of much of American health care.

In 1973, faced with the specter of the wealthy receiving life-saving dialysis while stingy insurance companies denied coverage to the poor, Congress passed a law amending the Social Security Act so that every patient in need of dialysis treatment would receive it. Nearly four decades later, this once-obscure program has ballooned, gobbling up nearly six percent of Medicare’s budget.

Today, Medicare spends $77,000 a year on each dialysis patient (most likely the highest rate in the world) and the US has the world’s highest fatality rate for dialysis patients. The story of how this came to pass illustrates a lot of the problems with US health care.

As Fields’ article makes clear, people respond to incentives. When the system compensates health care providers for each procedure performed – as the US health care system’s fee-for-service model generally does – you get a lot of treatment procedures done, at a high pricetag. Since its inception, Medicare’s dialysis program has paid treatment centers a flat fee for each patient treated without regard to the efficacy of treatment or health outcomes.

Thus, Medicare’s dialysis program produced a burgeoning number of clinics where people could receive treatment, but the treatment is, judged by worldwide health care standards, subpar. A higher percentage of Americans in dialysis treatment die than in any developed country. Fee-for-service means that treatment centers are just interested in completing and billing out procedures, even if their substandard treatment ultimately kills the patient who lays the golden egg.

A fee-for-service model also means that any outcome that does not get compensated falls by the wayside. Because treatment centers are paid for how many patients they treat and not for how healthy they keep the patients, it’s not uncommon for the the clinics to be dirty and infection-prone, their walls smeared with contaminated blood.

Because American health care professionals are mostly compensated on a fee-for-service basis (unlike in much of the rest of the world), American dialysis patients are more likely to suffer from complicating factors like diabetes and hypertension than patients elsewhere. The typical American doctor has no financial incentive for preventing his patients from developing Type II diabetes or hypertension, or for controlling those conditions. The typical American doctor is compensated only for seeing and treating those patients, so our dialysis patients are also less healthy than in the rest of the world.

Fee-for-service health care, as we have in the US, also dooms price controls to failure. As the price of dialysis machines fell, treatment centers were making money hand-over-fist as the treatment was less expensive to provide while the reimbursement rates remained high. Medicare realizing it could cute reimbursement rates, while still enabling operators to make a profit, did just that.

What happened? The use of certain expensive injectable drugs, such as Epogen – that are used to treat side effects – skyrocketed. Medicare was continuing to provide generous reimbursement rates for these injectable drugs so patients who did not need these drugs got them. Italy, which has the lowest dialysis mortality rate in the world, gives Epogen to half as many of its dialysis patients. Today, doses of Epogen are Medicare’s single highest pharmaceutical expenditure.

The US badly needs to move away from the fee-for-service model toward a model that provides incentives for high-quality, low cost care. The same Health Affairs study from a couple months ago that pegged the direct and indirect costs of medical malpractice lawsuits at two percent of our heath care spending, said that the cost of medical errors was dwarved by the costs added by fee-for-service.

The good news is that next year Medicare is rolling out a new reimbursement system. Treatment centers will no longer be able to bill separately for injectables. And we’ll see the debut of at least one outcome-based (rather than fee-based) metric: clinics could lose as much as two percent of their Medicare funding if they fail to meet certain minimal thresholds for anemia-management and dialysis-adequacy, as measured by patient blood tests.

It’s a modest start, but it’s a step in the right direction. And, in the meantime, let’s stop acting like American health care is going bankrupt compensating those who have been maimed and killed by medical errors.

ECRI Institute Releases List Of Top Ten Threats To Patient Safety

Last week we blogged about a new study published in The New England Journal of Medicine showing that patient safety has not improved in the ten years since the Institute of Medicine published its famous study showing that medical errors kill 98,000 Americans a year.

Last week we blogged about a new study published in The New England Journal of Medicine showing that patient safety has not improved in the ten years since the Institute of Medicine published its famous study showing that medical errors kill 98,000 Americans a year.

How to improve patient safey? This week the ECRI Institute released its fourth annual Top Ten list of threats to patient safety. They are:

1. Radiation Overdoses: A subject we’ve blogged about here, here and here.

2. Alarm Hazards: Whenever you go to a hospital, you hear dozens of alarms buzzing, alerting staff to problems with patients. The danger comes when nurses or doctors silence the alarms to stop the annoying ringing, or simply ignore them.

3. Cross-contamination from flexible endoscopes: Most infection problems are preventable, if attention is paid to them.

4. Radiation overdoses in CT scans: Again a subject we’ve blogged. See above.

5. Problems with medical records: Information Technology needs to improve so that patient records are more easily obtained and health care providers are working on interoperable systems.

6. Luer Connections: Luer Connections are important parts that hook up needles, catheters and tubes. When improperly connected, they can introduce improper gases or liquids into a patient’s bloodstream.

7. Overdosage through PCA infusion pumps: PCA pumps administer set doses painkillers. When misprogrammed, they can overdose a patient.

8. Needle sticks: They’re a problem that affects not only health care providers but also patients.

9. Surgical fires: Surgical fires are as common as wrong-site surgeries. In this week’s news was a gruesome case where a patient’s throat was set on fire during laser surgery.

10. Defibrillator problems: This problem of increasing urgency was added to the list this year.

Link Roundup

- A new NHTSA study reveals that, as police drug test increasing numbers of drivers in fatal accidents, the number of drivers found to be intoxicated is increasing. Right now, nearly two-thirds of drivers involved in fatal accidents are drug tested and eighteen percent of those test positive. One-third of drivers killed in fatal car accidents have drugs in their system.

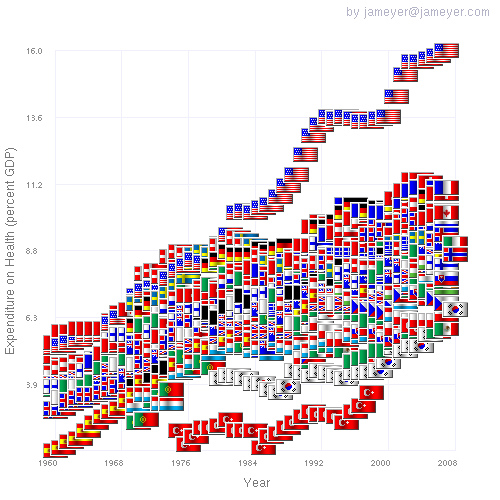

- A really amazing graphic showing how different countries’ spending on health care has increased from 1960-2008 as a percentage of their GDP:

(Hat tip to the creator of this graphic). You can’t blame that uptick on the medical malpractice lawyers.

- A new Vanity Fair article takes a hard look at a topic we’ve examined before: the outsourcing of clinical trials to countries in the developing world. (Hat tip Prof. Bernabe, who has been blogging this topic for some time).

Surprise, Surprise: Patient Safety Has Not Improved In Ten Years Since Landmark Study

According to a study published in the most recent issue of The New England Journal of Medicine, patient safety has not improved since a landmark study ten years ago that put the number of patient deaths due to medical error at 98,000 annually in American hospitals. That landmark study, conducted by The Institute of Medicine, also estimated that one million Americans each year are injured by non-fatal medical errors.

According to a study published in the most recent issue of The New England Journal of Medicine, patient safety has not improved since a landmark study ten years ago that put the number of patient deaths due to medical error at 98,000 annually in American hospitals. That landmark study, conducted by The Institute of Medicine, also estimated that one million Americans each year are injured by non-fatal medical errors.

Experts hoped that the shocking death tally in the Institute of Medicine study would spur improvements in patient safety. But, as the new research reveals, those hoped for improvements have not materialized.

The new research was done by looking at ten randomly selected hospitals in North Carolina, a state that was believed to be making strides in improving patient safety. The researchers studied 2,341 hospital admissions from 2002 to 2007 and found that medical errors were made in one quarter of the cases. Ten percent of those – or 2.5% of the total admissions – were the victims of potentially life-threatening medical errors.

Dr. Christopher P. Landrigan, lead author of the new study, says, “We were disappointed but not very surprised [by the results].”

How can doctors improve patient safety? Landrigan points to reducing the number of hours worked by sleep-deprived residents, following medical checklists and implementation of electronic medical records as important steps to take, all measures that we have blogged about here, here, here and here.

Landrigan also says that we need to create a nationwide system for reporting injuries due to medical errors. Such a system would help researchers identify areas of repeated mistakes.

Sources:

- “Temporal Trends in Rate of Patient Harm Resulting From Medical Care” (New England Journal of Medicine)

- “Study: No Improvement in Hospital Safety” (WebMD)

- “Study Finds No Progress In Safety at Hospitals” (New York Times)

Are Medical Malpractice Lawsuits To Blame For Doctors Shirking Responsibility For Their Errors?

The blog KevinMD.com features a blog post about the story of Dr. Ring – whom we had previously blogged about here.

Dr. Pho (aka KevinMD) claims that Dr. Ring’s story is getting such heavy media attention because it’s a rarity – a practitioner owning up to a medical error in a public manner. Dr. Pho says that doctors admitting mistakes is a rarity because doctors are afraid of getting sued for admitting their mistakes. The medical malpractice system leads to concealing mistakes, Dr. Pho claims, and that’s bad for patient safety.

As one commenter to the blog post notes, “Doctors have a multitude of reasons to hide their errors, rather than the fear of litigation. There’s bad reputation, loss of self-respect, difficulty of admitting error to patients, loss of patients, and other financial injuries-as well as professional ostracism.”

The reputational harm of admitting mistakes is probably the reason why so few doctors admit mistakes even after the insurance carriers have paid out claims and the doctor no longer faces any liability whatsoever for his mistake. If Dr. Pho’s theory explained things, doctors would freely own up to mistakes once they had obtained a release of claims for settling a case. But they don’t (generally).

I think doctors don’t admit mistakes because they’re, well, doctors. As Dr. James Bagian, the VA’s chief of patient safety, notes here, doctors trace their heritage back to Hippocrates, not the trial-and-error values of the Scientific Revolution. Doctors aren’t scientists; they are healers, and this means that they are loathe to admit their mistakes.

It’s also psychologically a lot harder for a doctor to admit a mistake than a research scientist. When laboratory scientists make mistakes, the only real world effect normally is that they’ve wasted their time chasing a hypothesis that did not pan out. When doctors make mistakes, there’s a real human being, one they’ve met and know and cared for, whom they’ve hurt.

As Dr. Pho is aware, there is evidence suggesting that doctors who admit to mistakes uprfront are less likely to ultimately be sued for medical malpractice. And insurance companies study medical malpractice claims to try and develop ways of avoiding repeating the same mistakes.

Dr. Pho may be right that our medical malpractice system should be less adversarial. But fear of being sued is not the main reason, or even a substantial reason, why doctors are not forthcoming about mistakes.

The Future Of American Health Care: Nurse-Based Care

In order to control the unsustainable increases in the cost of our health care, Americans are going to have to transform the doctor-based model of care. Our doctors are already, by a wide margin, the highest paid in the world.

In order to control the unsustainable increases in the cost of our health care, Americans are going to have to transform the doctor-based model of care. Our doctors are already, by a wide margin, the highest paid in the world.

Doctors’ high pay is not some natural occurrence: the American Medical Association keeps a tight grip on the number of accredited medical schools and thereby artificially limits the number of doctors entering practice. Controlling the supply of doctors has the effect of driving up the price for their services.

The AMA’s policy has created an artificial scarcity of doctors. Currently, there is a shortage of 7,000 physicians, mainly in primary care. Over the next ten years one-third of physicians will retire, and the shortage will increase to 100,000 physicians across all specialties.

To succeed in driving down the cost of health care, we are either going to have to produce more doctors or reduce the demand for their services. And it appears that the direction we are moving in is reducing the demand for doctors’ services by allocating more of their customary responsibilities to nurses.

The Institute of Medicine recently issued a report on the subject entitled, “The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health.” And this week The Times featured a great article on the topic.

A lot of the doctors I speak to believe that in the next decade or so many patients will begin seeing nurse practitioners as their primary care. A move away from doctor-based care may benefit us all if it helps us save on health care.

But I would like to see someone loosen the AMA’s stranglehold on the supply of physicians. A few months back Matt Yglesias had a great series of posts on eliminating artificial barriers to entry into a variety of professions, including medicine. In a perfect world, we wouldn’t be facing a shortage of doctors at all.

Reforming Medical Culture Begins With The Elite

We’ve blogged a lot about how reforming the way that doctors and hospitals deal with medical errors requires a cultural transformation. Doctors need to stop regarding errors as signs of incompetence or intellectual weakness and need to adopt the ethos of engineering culture: mistakes are going to be made, so let’s be open and forthright about them and learn from them.

We’ve blogged a lot about how reforming the way that doctors and hospitals deal with medical errors requires a cultural transformation. Doctors need to stop regarding errors as signs of incompetence or intellectual weakness and need to adopt the ethos of engineering culture: mistakes are going to be made, so let’s be open and forthright about them and learn from them.

We’ve seen some movement in that direction, with medicine adopting some of the safety engineering principles of the aviation industry. But how does medicine get there? The answer is that it gets there when its elite, the profession’s best-credentialed and most respected members, own up to their mistakes and stop pretending that they’re a breed apart who don’t make mistakes.

Cultural change comes from doctors like Peter Pronovost, a MacArthur “genius grant” recipient and one of the leading clinical figures of his generation, frankly admitting that he made a grave medical error as a young physician (as previously blogged about here). This week we saw another crack in the wall as The New England Journal of Medicine published an article by Massachusetts General Hospital surgeon Peter Ring about an operation that he performed on the wrong hand of a patient in 2008.

As a Harvard-educated surgeon at Mass General Hospital (one of the world’s most renowned hospitals), Dr. Ring is, like Dr. Pronovost, a card-carrying member of the health care profession’s elite. Although Dr. Ring speculates that such a public airing of his mistake may harm his reputation among colleagues, it’s more likely to affect patient perception of him, as lay patients are generally much more ignorant of where their doctors stand in the professional hierarchy.

Dr. Ring deserves commendation for coming forward and helping to reverse the centuries-old tradition of doctors denying mistakes. When people at the pinnacle of their profession, like Dr. Pronovost and Dr. Ring admit that they too make mistakes, like us lesser mortals, it opens up space for those beneath them in the profession’s pecking order – young doctors, lesser-credentialed doctors – to admit their mistakes.

When we have a culture where doctors admit mistakes and make sure their colleagues learn from their errors, we’ll see a lot fewer “wrong site” surgeries and vastly improved patient safety.

You should read Dr. Ring’s account of the surgery here; it provides a nice illustration of how medical errors often have a multitude of causes and how responsibility is often spread throughout the operating room and even outside of it.

Massachusetts Poised To Abandon Fee-For-Service Medicine

As reported by the American Medical Association (hat tip Tyler Cowen), Massachusetts is poised to enact legislation sounding the death knell of fee-for-service medicine as soon as 2011. Fee-for-service medicine refers to the system of paying doctors according to the number of services that they perform rather than by some other metric. So, for example, under the fee-for-service model (which dominates American health care), doctors are paid for each and every test and procedure that they perform. This incentive structure obviously has an effect of encouraging doctors to order more and more tests and procedures as such overtreatment is more lucrative than the alternative.

As reported by the American Medical Association (hat tip Tyler Cowen), Massachusetts is poised to enact legislation sounding the death knell of fee-for-service medicine as soon as 2011. Fee-for-service medicine refers to the system of paying doctors according to the number of services that they perform rather than by some other metric. So, for example, under the fee-for-service model (which dominates American health care), doctors are paid for each and every test and procedure that they perform. This incentive structure obviously has an effect of encouraging doctors to order more and more tests and procedures as such overtreatment is more lucrative than the alternative.

As I’ve blogged about previously, a recent article published in the journal Health Affairs estimates that the direct and indirect costs of medical malpractice lawsuits add only 2.4% percent annually to our nation’s health care tab (while compensating those injured by medical malpractice). The article stated that the cost of medical malpractice lawsuits is dwarfed by the expenses attributable to the fee-for-service model.

Under the Massachusetts legislation that could be introduced as soon as January 5, 2011, health insurers would begin paying doctors under a “global payment system” – i.e., paying doctors a flat fee based upon the number of patients seen monthly, with adjustments made for patients’ ages and health conditions. It will be interesting to see what effect this new legislation will have on health care costs.